As hitting the 1.5-degree target gets harder, we need to focus more on adaption, coping with what is going to get thrown at us.

While we talk a lot about climate mitigation, it's important to recognise that for many places it's climate adaptation that is now needed. This covers not only flood and hurricane protection, but also what happens after a disaster, as we try to get local economies back on their feet as quickly as possible.

What is the big investing theme? The UN estimates that climate adaptation spending, just in developing countries, could reach $300bn by 2030. This is on top of the tens of billions being spent by national and regional governments in developed countries. This covers a range of investment themes, including construction of flood defenses, building resilience into our essential services, and enhancing disaster responses.

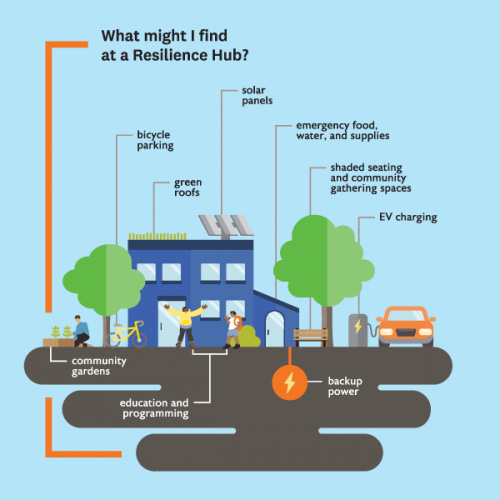

In a recently published article RMI discusses the last issue, weathering climate disasters with resilience hubs. Resilience hubs offer local governments a powerful means of supporting vulnerable populations before, during, and after an extreme weather event or other disasters. Depending on the needs of the communities where hubs are located, they can support resilience across five foundational areas — ensuring reliable power, coordinating communication, providing dependable facilities, managing operations, and offering valuable services and programming.

Enhancing energy efficiency at a resilience hub can increase “hours of safety” — a measurement of how long a building can maintain a safe, comfortable temperature when the power goes out. Resilience hubs with solar and storage can be especially impactful for disadvantaged communities. In the case of Storm Uri (Texas 2021) low-income communities who did not live on “critical circuits” with hospitals or other critical infrastructure experienced longer power outages — some up to four days — as the limited power available was prioritized elsewhere.

In September, Hurricane Fiona devasted Puerto Rico's electricity grid. Striking landfall just three days before the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria that caused the longest blackout in US history, Fiona’s destruction to the grid was a stark reminder that the recovery efforts after Maria were not enough. Since 2017 Puerto Rico has had a hankering for resilient microgrids. This desire is only growing during the post Hurricane Fiona recovery as solar has been a lifeline.

And this is not just impacting Puerto Rico. Julien Gargani looked at the impact of major hurricanes on the islands of the Caribbean - identifying that after the major hurricanes, electricity energy production showed a slow recovery followed by a stable phase lasting several months, corresponding to c. 75% of the initial electricity production.

And this is not a new theme. Back in 2012, analysts were writing about how natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina in the U.S., and the earthquake off the coast of Japan in 2011 had profound effects on the electricity grid. In a 2009 report, the U.S. Department of Energy stated that Katrina caused approximately 2.7 million customers to lose power, and that it took four to eight weeks to restore electricity to all but the worst affected households in the Gulf region.

While official figures say that the freezing conditions that followed massive power failures in Texas during Hurricane Uri in 2021 caused 151 deaths, a study of state mortality patterns suggested the figure may have been as high as 700. And it's not just about losing electricity, although that is often the most visible impact. Sources cited by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimated the storm-related financial losses across Texas ranged from $80 billion to $130 billion. And a study by the University of Houston, Hobby School of Public Affairs found that three-quarters of respondents had difficulty procuring food and groceries.

Resilience hubs can literally be a lifeline. They can create spaces where people can come to get information, access the internet, charge their phones (and even their cars), get essential food and water, stay warm, and get medical assistance. And they can also serve a wider role during non-disaster periods, being a hub for the local residents, based around meeting spaces, community gardens and education services.

One obvious approach is to make these hubs modular - allowing construction costs to be minimised, and build times to be shortened. And we are going to need thousands of these around the world.