When it rains, many of our wastewater treatment processes get overwhelmed, as they are actually combined sewers - not just collecting the sewage and wastewater from buildings and industry, but also stormwater runoff. If all of this water was allowed to enter the sewage treatment plant, it would be flooded and potentially suffer extensive damage. So the excess water is diverted around the treatment plant, and spilled directly into our rivers, lakes and the sea.

As with many of our sustainability transitions, the cost of the new infrastructure and systems we need to build to replace the 'old ways' of doing things is massive. We need to find ways of funding this investment in the most cost effective manner - which often means new and innovative solutions. This is especially true for waste water. Here, its not just the case of building more treatment holding facilities, although that plays a part. There are also alternative greener solutions, and its starting to look as if they have a strong financial case.

Untreated sewage being dumped in our rivers and oceans is moving up the social and political agenda across Europe - nowhere more so than the UK. The industry groups are saying we can fix this, with more hard infrastructure. The cost of this - apparently billions of £, leading to materially higher water bills. And this will only partly solve the problem.

But is this really the only way to fix this ?

We think of treating our sewage as being an important indicator of becoming a developed country. But across the world, in locations as far apart as Paris and Tokyo, what is known as fecal contamination is a major problem. This is causing damage to our environment and our health.

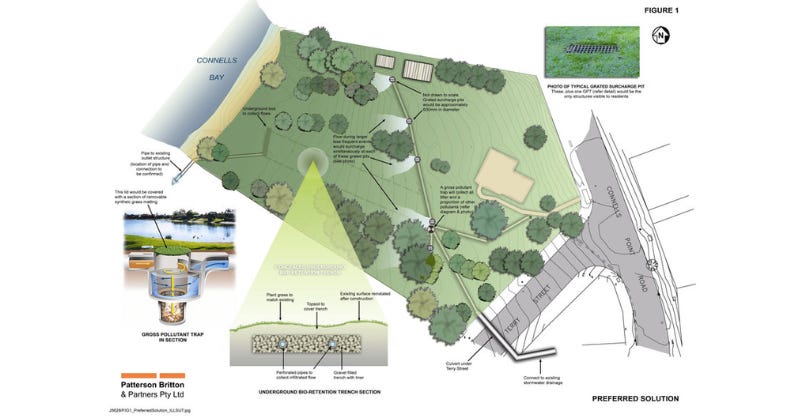

The challenge is to find a cost effective solution. The traditional solution has been to build even more treatment and storage infrastructure. But, more recently, new and innovative green approaches have been shown to potentially offer better value for money. One name for them is sponge cities - finding ways of slowing down the water flow so that less dumping or overflows take place.

These approaches have enormous environmental, social and economic benefits. The environmental benefits include reducing the pollutant loads and improving the water quality of the receiving water, protecting the existing natural and ecological processes, and maintaining the natural hydrologic cycle and aquatic ecosystems.

They also provide social benefits that include protecting public health, improving the landscape and aesthetics, providing green spaces and increasing biodiversity. Plus, they provide economic benefits by being cost-effective when compared to conventional 'grey' strategies. They are not always the panacea, but surely they should be part of the solution.

So why hasn't this happened. We suggest part of the reason is the way that our regulatory systems work - incentivising the utilities to build more assets. But the other reason is that using green approaches such as sponge cities requires us to co-ordinate the work of the utilities with local planners, working with communities.

That's hard, its easier just to set rules. And, to be fair, as a society we are not demanding enough. We need to get more involved. As we do with electricity, with transport and with agriculture.