Sustainable Investing weekly blog: 1st April 2022 (issue 32)

Story tags for this blog

fertiliser, diesel bans, green cement, cyber standards & battery storage

Our weekly summary of the key news stories, developments, and reports that are impacting investing in the wider transition to net zero carbon and a greener/fairer society.

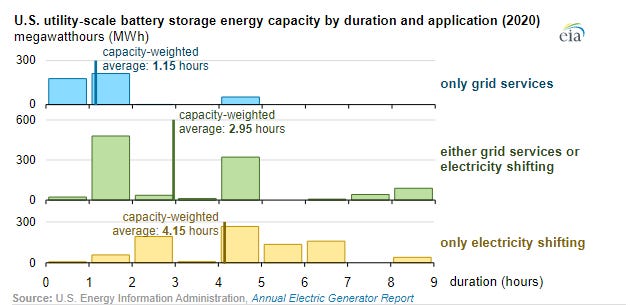

It seems wrong to publish on the 1st April, I reassure myself that it doesn’t actually go out until Sunday, so that’s ok ! This week we start in Agriculture (as promised last week), examining the possible mid term impact of higher gas prices on how much fertiliser we might use in the future. Next up, in Transport, we look at how ready are we for the rapidly approaching bans on diesel HGV’s in some European cities, then in Built Environment, we report on the “world’s first clinker-free cement (aka green). Finally, in Distributed Electricity, we flag moves by the NREL to establish cyber standards for distributed energy resources – this may sound boring & geeky, but its actually going to be really important. In our One Last Thought, we cover a US EIA report on how utility scale battery storage is stretching out its duration.

Important - this blog does not constitute Investment Research as defined in COBS 12.2.17 of the FCA’s Handbook of Rules and Guidance (“FCA Rules”). See the end of this blog for important terms of use.

Top story : Are we really looking at a global food crisis ?

,How the global fertiliser shortage is going to affect food (The Conversation)

Main points of the story as published

We are currently witnessing the beginning of a global food crisis, driven by the knock-on effects of a pandemic and more recently the rise in fuel prices and the conflict in Ukraine. There were already clear logistical issues with moving grain and food around the globe, which will now be considerably worse as a result of the war. But a more subtle relationship sits with the link to the nutrients needed to drive high crop yields and quality worldwide.

Fertiliser inputs to farming systems represent one of the largest single variable costs of producing a crop. When investing in fertiliser, a farmer must balance the return on this investment through the price they receive at harvest. This calculation between the cost of fertiliser and the value of the crop produced – the “breakeven ratio” – is typically around six for a cereal crop (6kg of grain needed to pay for 1kg of nitrogen fertiliser), but with the rise in fertiliser prices it is currently around ten. To remain profitable, farmers will need to keep a particularly close eye on production costs, and potentially use less fertiliser. However using less fertiliser will reduce yields and quality, adding to pressure on the food system as a whole.

The latest sharp rise in fuel prices is directly impacting on the prices of fertilisers, which helps to explain why the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) food price index reached its highest ever value in February. Russia and Ukraine are major producers and suppliers of fertilisers and their raw materials. For example, Norwegian group Yara, the biggest producer and supplier of fertilisers in Europe, makes much of its product in Ukraine. Russia is responsible for nearly a tenth of global nitrogen fertiliser production.

Our take on this

This is not the only article to suggest that the war in the Ukraine will potentially tip the world’s food systems materially out of balance, with Carbon Brief reporting that the chief economist of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) told the Guardian that the conflict “could tip the global food system into disaster”. At a local level, the crisis is showing up in fertiliser prices paid by farmers, with the latest AHDB average price indications for UK fertilisers suggesting prices are up by c. 130% y/y for ammonia nitrate & granular urea, which is creating material pressures on both food prices and farmer incomes.

Looking beyond the immediate crisis, our questions are around what this might mean for fertiliser use in the mid term. How much will this push farmers towards either making do with less fertiliser but applied only where needed (using agtech/precision ag) or switching to alternatives (including “natural fertiliser” & biologicals). This is a topic we have done a bit of digging into & we believe both markets could become material over the next five years (so soon).

We have talked about the potential for precision ag before (in the context of the robotics and smart equipment/tractor market) – so today we focus on alternatives to traditional fossil fuel produced nitrogen fertilisers.

Before we look at some of the alternatives, its important to repeat our view is that, leaving aside price, its the over use of fertiliser that is the real problem, not how it is made. Back in Jan, we highlighted the link between the loss of soil organic carbon & the excessive use of nitrogen fertilisers.

The UK government has recently announced that they intend to start paying farmers to use green fertiliser, although the scheme currently lacks the all important detail. A recent sifted article discussed a number of interesting alternate approaches by start ups including adding nitrogen to livestock manure, the use of human urine, and the extraction of mineral stimulants such as zinc, manganese & copper from alkaline batteries. But its not just early start up technology. Our recent research highlighted companies such as PivotBio (producing microbial based fertilisers – the company completed its $430m Series D funding in July) and further back up the value chain, some of the microbe products from the listed company Novozymes.

We see biological’s as being the solution that can work at the required scale to replace material amounts of fossil fuel derived nitrogen fertiliser. Interest in biologicals is being driven by a host of factors including increasing consumer & regulatory pressures and the re-discovery of the importance of soil health (and regenerative agriculture).

Clearly, the use of alternatives to traditional fossil fuel based nitrogen fertilisers is still small scale, but its something companies (& their investors) exposed to this space need to watch out for. We partly accept the argument that emerging markets will be important for traditional fertiliser companies for many years. But, change can happen fast, especially when driven by a combination of high costs, social pressure and regulation.

Transport – how ready are we for city centre diesel bans ?

,Can cities still feed themselves when diesel trucks are banned (The Grocer)

Main points of the story as published

Paris is ousting the vehicles in 2024. London, Oxford, and Bristol won’t be far behind. Diesel lorries cannot last much longer, but is the sector ready for the shift? Under an EU agreement signed in 2011, all European cities have pledged to have CO2-free urban logistics by 2030, pushing the likes of London to expand its Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) – named “one of the world’s most radical urban policies” by the Centre for London think tank – and Oxford to launch the UK’s first zero emission zone last year.

The intention is to crack down on toxic air pollution and move further towards net zero, which will be a crucial part of tackling the accelerating climate crisis. Road freight accounted for a fifth of all London’s nitrous oxide pollution in 2016, according to the London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory – and it’s having a deadly effect on people. In 2019, between 3,600 and 4,000 Londoners died due to human-made emissions, with road transport the primary factor, according to research commissioned by Transport for London (TfL) and the Greater London Authority.

According to TfL, 89% of goods brought into London come on the back of a lorry, almost every single one of them powered by diesel. It is a similar case across the UK, Europe, and most of the world.

Our take on this

This issue has been written about for a while – as evidenced by this 2019 article. A recent T&E report also highlighted that cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam want to reach zero emission urban logistics by 2025 – which would require for instance all 3,500 trucks and 25,000 vans that drive into the city of Amsterdam to electrify.

The debate is often framed around HGV’s, as evidenced by this article This is understandable in a way as they are the form of road transport we are most familiar with. For HGV’s, the debate generally revolves around issues such as model availability, cost, and range. On availability, it seems a fair point. While some fully electric HGV’s are already available and ranges are a being beefed up, its generally c. 2023 when they are due to roll off the production line at scale. Which is really tight to the 2025 target. Plus, some of the push back suggests that for long haul HGV’s, the solution may never be fully electric, with hydrogen, fuel cells and LPG all talked about.

We think this partly misses the point. Smaller trucks & vans with 200 to 300 km of range can cover most of the urban and regional delivery requirements. In the EU, almost half (47%) of road freight kilometers are trips of less than 300 km and they represent 90% of the transport operations. Plus, c. 80% of them could recharge at a depot, so only limited charging/range issues. Plus, on cost, electric vans are shown to be cheaper than diesel for all users.

But availability is still an issue, with T&E reporting that the supply of electric vans will continue to fall short for the rest of the 2020s unless the EU’s proposed van CO2 targets are significantly increased. Just 3% of new van sales were electric in 2021, marginally up from 2% in 2019. The EU’s proposed CO2 rules — which leave targets in the 2020s untouched — don’t require manufacturers to increase sales of electric vans above a 10% share before the end of the decade. This is clearly a conflict with the plans of an increasing number of cities.

The solution is known, electric vans work. We just need to find ways to push more vans and light trucks off the production lines. In this debate, the long haul HGV element is a red herring, we don’t need complicated new technologies. But, until the regulation gets tougher, its hard to see the cities hitting their non diesel delivery targets.

Is green cement closer than we think ?

,Hoffman “green” cement validated by CSTB (Company release)

Main points of the story as published

Hoffmann Green Cement Technologies, an industrial player committed to decarbonising the construction sector that designs and distributes innovative clinker-free cement, announces that its H-UKR cement has become the first clinker-free cement in the world to be validated by the CSTB (Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment, i.e. Scientific and Technical Center for Building) for structural applications on all types of structures.

Following four years of physical, chemical and mechanical trials, H-UKR cement has benefited from Technical Appraisal (type ‘A’ ATEx) from the CSTB, the public company that guarantees the quality and safety of buildings. This evaluation covers a very large number of buildings from individual homes to tower blocks for various structural applications (floors, shells, beams, columns, etc.) The design of concrete structures based on H-UKR cement is undertaken in accordance with Eurocode 2 and Eurocode 8, design standards recognised in France and Europe.

Our take on this

According to industry analysts, some 30 billion metric tons of concrete is used globally each year to build bridges, roads, highways, high-rise buildings, sewage systems, and more. The high-temperature process for manufacturing cement accounts for roughly 8% of the world’s anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions and consumes 2–3% of the global energy supply, according to the International Energy Agency. So finding a way to cut this industries CO2 emissions is a big deal.

The current standard product is known as portland cement. This is made using a high-temperature production process that converts calcium carbonate (CaCO3), the principal component of limestone, to calcium oxide (CaO), or lime, releasing CO2. That simple reaction is the source of about half the CO2 emissions in cement manufacturing. The bulk of the other half of the emissions comes from burning fossil fuels—often coal—to heat the kiln. Overall, the process emits more than 800 kg of CO2 for every metric ton of cement produced.

To produce cement, manufacturers grind the resulting product, known as clinker, and mix it with gypsum, to prevent the powder from clumping and to control the subsequent reaction with water. So, if we could make cement without clinker, its possible to materially cut CO2 emissions. In 2020, Cemex launched Vertua Ultra Zero, a geopolymer clinker-free concrete, in which an alkali-activated alumina-silicate matrix serves as the binder. The company claims that this product reduces the carbon footprint of concrete by 70%. More recently Ecocem’s Exegy ultra low carbon concrete (developed along with Vinci Construction) was used to create prefabricated units for the Grand Paris Express. They also claim a c. 70% CO2 emission reductions, when compared with traditional concrete.

The Hoffman product referred to in the article appears to another product that has achieved technical validation in a range of applications including its use in individual homes and tower blocks (including floors, shells, beams & columns). The big barrier to overcome is still cost. A Sept 2020 article suggests that the Cemex product could work at a carbon price of c. $30/ton of CO2. This assumes that some form of carbon pricing becomes widespread, moving away from the occasional regional scheme.

NREL to work on cyber security standards for distributed energy

,Cyber security standards for distributed energy (NREL)

Main points of the story as published

NREL’s work involves participation in broad stakeholder committees to create universal guidelines across all applications of DER cybersecurity. NREL is helping lead a revision of IEEE Standard 1547.3, the guidance for cybersecurity of DERs that interface with the power system, as well as steering a certification standard alongside Underwriters Laboratories Inc. (UL) for the next generation of DER hardware. Such standards development will promote wider awareness around the current state of cybersecurity standards and deliver a well-tested reference for DER cybersecurity across the industry.

Our take on this

Regular readers will know that we see distributed energy as being the most likely future. Electricity grids, so transmission and distribution, will remain important for decades. But progress is updating them to cope with the extra demands of renewable generation variability, two ways flows, and enabling the use of demand management tools, are just not moving fast enough. This opens up an opportunity for distributed energy, generated close to its point of use. This covers everything from microgrids, through to local Combined Heat & Power (CHP) and district heating. For these to work, we need digitisation and vastly improved communication systems. Which brings us back to cyber security – which is why moves such as this one are so important.

One last thought

,,Duration of utility scale batteries depends on how they are used (EIA)

At the end of 2021, the United States had 4,605 megawatts (MW) of operational utility-scale battery storage power capacity, according to the EIA’s latest Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory. Batteries used for grid services have relatively short average durations. A battery’s average duration is the amount of time a battery can contribute electricity until it runs out. But batteries used for electricity load shifting have relatively long duration’s. The chart above (bottom bars) shows duration’s of over 4 hours. Why is this important – because the debate about batteries needs to move on. They used to be thought of as something that works best covering shorter periods, say up to 1-2 hours. This is rapidly changing and they are increasing able to handle periods of up to 8-9 hours, so well after the sun goes down.

Some process and semi legal stuff . The format of the blog is simple. First our summary of the key points of the story (click on the green link to read the original) and then what we think it means for investors (asset owners, asset managers and companies). We are really keen that you read the original report or article. Lots of people out there are doing some really interesting and valuable work and part of purpose of these blogs is to bring this to your attention, while at the same time giving it context.

The focus is on news flow that we think should change the markets perception of the investment risks and opportunities coming from the big themes around the climate transitions and ESG. So not the place to come to for news about the latest ESG or net zero promise, or that has already been well covered in say the FT. Our approach is unashamedly long term, this is a multi decade investment theme. So we ignore short term noise.

Click Here for Important Information and Disclaimers

Finally, and very importantly, nothing in this blog should be construed as providing investment advice. For company and/or fund specific investing advice and recommendations, you need to look elsewhere. In more formal language, this blog does not constitute Investment Research as defined in COBS 12.2.17 of the FCA’s Handbook of Rules and Guidance (“FCA Rules”).