Topics - agricultural emissions reform might lead to fewer farmers, using nudges in smart cities to improve safety, will tenants become responsible for making buildings low carbon, flow batteries as a long term energy storage technology, the growth of resale in luxury (embrace or fight ?) and our approach to modern slavery doesn’t seem to be working despite the surge in ESG funds and revisiting orphan O&G wells.

The Sustainable Investor - our weekly summary of the key news stories, developments, and reports that are impacting investing in sustainability, the wider climate related transitions, and a greener/fairer society. The important word in this sentence is investing - it’s perfectly possible to use our capital to support sustainability, and still earn a fair financial return.

If you want to be helped to move forward on the long term issues being faced by sustainable investors, please subscribe and support our work or even better subscribe and share (see the button at the end of the blog).

This week’s blog has a bit of a built environment theme. It’s a tough theme for investors, relying as it sometimes does on government action and regulation. Our top story covers the fully blown fuss over reform of agricultural emissions. It’s been challenging for Europe for some time, now New Zealand and The Netherlands seem to be grasping the nettle. We then shift to a small-scale trial of technology to improve cyclist safety that could have big global implications. Then it’s an examination of who pays, and is responsible for in a reporting sense, for buildings emission reductions, before looking at the possible role of flow batteries as a long-term storage technology, helping renewable generation systems keep the lights on over extended periods. We end up with an examination of the role of resale in the luxury industry, why, despite the surge in ESG funds we seem unable to stop modern slavery growing and a quick revisit on the topic of orphan O&G wells.

Agriculture: might we end up with fewer farmers ?

Pricing agricultural emissions - final public consultation (NZ Government)

What is the big investing theme - reforming agriculture is a big deal, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, environmental impact, food security and rural society. But it’s going to requirement massive social and economic change and disruption, to production methods, to supply chains and to employment. It’s not clear that the political will to change fast enough really exists, which could mean faster and more dramatic change needs to come in the future.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

The New Zealand Government has released the details of its plans to introduce a carbon pricing scheme for its agriculture sector. The launch of the scheme is planned for early 2023, after a short consultation process on its final elements. This is intended to be the last stage of a process that started c. 20 years ago, but that only really gained momentum three years ago, when the government, the farming community and the indigenous Maori, set up the – Primary Sector Climate Action Partnership (He Waka Eke Noa).

Under the plan, agricultural business owners would be responsible for reporting and paying for emissions depending on the type of emission. The prices would be adjusted regularly based on progress towards the proposed goals. The funds gathered under the plan would then be used to fund research and develop tools and technology to further reduce agricultural emissions.

Emission prices will vary depending on the farm size, livestock numbers and production, and nitrogen fertiliser use. In addition, the Government proposes an incentive payment for a range of on-farm emissions reduction technologies and practices when taken up by farmers and growers. The plan estimates that the introduction of agricultural emissions pricing will reduce biogenic methane emissions to 10 percent below their 2017 levels as soon as 2030.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

It’s not just New Zealand that is impacted by these pressures, other countries, most prominently The Netherlands, are also having to face up to similar challenges. This is an issue that will only get harder and harder to fix the longer it gets left.

To be clear, New Zealand is in a slightly unusual situation, with roughly half of its GHG emissions coming from agriculture. So, it’s not surprising that they seem to be setting the pace on decarbonising this important sector. Perhaps slightly more surprising, given their involvement in the process, is the reaction of the farmers industry group Federated Farmers, who claim the plan would "rip the guts out of small town New Zealand" and see farms replaced with trees.

The New Zealand Government has committed to a 10% reduction in methane emissions from agriculture and landfills by 2030, going up to a 24-47% reduction by 2050, both compared to 2017 levels. Among the decisions still to be made, the big one is the treatment of pricing synthetic nitrogen fertiliser emissions, with the two options being pricing at farm-level and pulling manufacturers and importers into the Emissions Trading System (ETS).

We are guessing that pretty much every country with a large agricultural sector is watching progress on this very closely. Estimates indicate that net global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, forestry, and other land use were over 8 billion metric tons of CO 2 equivalent, or about 24% of total global greenhouse gas emissions. Success of the policy in New Zealand is likely to encourage other governments to at least consider similar changes, although it remains a politically divisive issue.

The other big example of this is the Netherlands, where the government plans to slash nitrogen emissions in half by 2030. As part of the coalition agreement, €25bn has been set aside to deal with the “Dutch nitrogen crisis”. In terms of nitrogen related impacts, agriculture is the main culprit. It has been known for decades that the country’s growing livestock herd is causing environmental damage. Yet, policymakers did too little, too late. Now, drastic change is needed.

The plan involves a drastic reduction of livestock by one-third over the next eight years. It wants to reach that goal by either buying out farmers, relocating farms that are close to vulnerable natural areas, or making farms more sustainable. While ideally this should happen voluntarily, the coalition agreement says if farmers refuse to cooperate, forced buyouts could be on the table.

The government estimate 11,200 farms will have to close and another 17,600 farmers will have to significantly reduce their livestock. As we said in the theme summary at the top of this story, the changes necessary to hit the targets many governments are setting will require massive social and economic change and disruption, to production methods, to supply chains and to employment. Given this the protests are not surprising.

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

Among the big trade offs in the reform of agricultural practices are the issues of food security and rural employment and how they mesh with continuing farm subsidies. Obviously, every country is different, but we actually have some real-world experience that sometimes gets forgotten. In the 1980’s, the New Zealand Government pursued a policy of an almost total elimination of farm subsidies. This was a massive change. For instance, it is estimated that at the time 40% of the gross revenues of beef and sheep farmers came from government subsidies.

Despite fears that famers would suffer and “walk off the land in vast numbers” a 2001 report by the IEA found that “the agricultural markets did adjust and that farmers did not end up bearing all the costs of reforms.’ While incomes dropped after the reforms were introduced, farmers then adapted to their new environment. But the adjustment in product and factor markets took about six years. Farmland prices fell after the reforms but have now returned to ‘… a normal relationship with product earnings.’

In the longer term, the removal of subsidies was a catalyst for productivity gains. New Zealand farmers reduced their costs, diversified land use, looked for non-agricultural sources of income, and developed new products. Farmers became more attracted to economically viable activities. Agricultural production stagnated in the years leading up to the reforms, but since then production has increased significantly faster than in other sectors of the New Zealand economy.

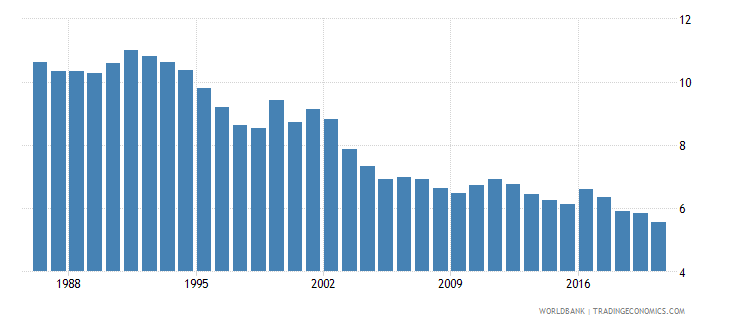

But and this is potentially a big but, as the chart above shows, agricultural employment in the country has continued to fall, from a high of over 10% in the mid 1980’s to c. 5.5% now. Yes, this is part of a worldwide trend, but that is still a big loss of jobs for rural communities, where alternative employment can be hard to find.

Smart Cities: Cycle-activated signage a nudge in the right direction

Cycle activated signage in Glasgow (SmartCities World)

What is the big investing theme - while many of the things we need to do to decarbonise our built environment are big (heat pumps, building insulation, EV charging etc) it’s easy to forget that many are also small and local. These often use smart technology in clever ways, making moving around our cities easier and safer. And lots of small and local can become a material investment opportunity, not just for installation, but also operations and maintenance.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

Solar-powered LED warning signs have been installed by Glasgow City Council to alert drivers to the presence of cyclists following on from a successful pilot. The system trial, at the junction of Berkeley Street and Claremont Street, saw a fall in the percentage of “conflicts” between drivers and cyclists.

The council has used smart sensor technology on previous projects and the roll-out will focus on locations where sight lines are sub-optimal, for example at side junctions or building entrances.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

More than half of all road traffic accidents involve vulnerable road users, i.e. pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists. Globally in 2019, there were more than 450,000 pedestrians, almost 65,000 cyclists and over 222,000 motorcyclists killed in road traffic accidents. Middle-income countries make up more than 80% of those vulnerable road user deaths with 8% from low-income (the latter due to the greatly reduced road infrastructure). Road traffic crashes cost most countries three percent of their GDP.

Another Glasgow scheme, the Ultra-Smart Cycle System, involved the leader of a schoolchildren’s bus bike being equipped with a device that could be pressed when approaching a junction, setting off a specially timed traffic light cycle that would hold traffic for 45 seconds allowing the children to cycle through safely. The device, developed by Sm@rt Technology uses military-grade encryption.

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

Incremental safety measures can have meaningful impacts but they also need to be appropriate for the location. The compulsory use of daytime running lights (DRL) on motor-vehicles in Nordic countries led to reductions in daytime accidents. For example, in Denmark studies conducted a few years after the rules introduction (Hansen, L.K. 1993), found six to seven percent reductions in daytime multiple-vehicle crashes and 34-37 percent reductions in left-turn crashes (into front of oncoming vehicles). Interestingly whilst it also reduced vehicle-to-cyclist crashes by about four percent, it actually increased vehicle-to-pedestrian crashes by 16 percent. US studies found no statistical benefit with the exception of light trucks and vans, possibly due to the brighter climate. A 2005 study looking at DRLs on cycles, found that the incidence rate was 19% lower for cyclists with permanent running lights mounted.

With technological solutions such as DRLs or additional signage, cost considerations in terms of money and energy usage as well as utility are important. For example, DRLs would draw on the engine's power and so low-cost solutions such as LED running lights would be a consideration, but brightness levels need to be appropriate (i.e. not so high!). In the case of this Glasgow scheme, the use of renewable energy to generate the electricity helps to reduce rollout costs.

Where solutions to improve sustainability are behavioural, often wholesale changes are so overwhelming as to be rejected outright. Professor Alex Edmans, in a lecture for the Gresham Institute talked about status quo stemming from inertia (it takes effort to make a decision) and conformity bias (taking cues from others’ actions even if uninformative). The new cycle signage in Glasgow is an example of a ‘nudge’ made popular in a 2008 book by behavioural economist Richard Thaler. Whilst there have been some debate about their effectiveness overall, there are other examples where small nudges in behaviour can help us be more sustainable. For example, a Manchester Metropolitan University 12-week study found that by moving the Coke Zero icon on digital menus of more than 500 stores from the third to first position, while moving the regular Coca-Cola icon from first to last, led to increased sales of Coke Zero by 30% and decreased sales of Coca-Cola by 7%.

Beyond consumer health, the theory could also be used to inform strategies aiming to encourage people to make more environmentally-sound choices. Whether that’s charging slightly more for products which involve single-use plastics (such as surcharges on disposable coffee cups), making sustainably sourced clothing a social status symbol, or making it more difficult for people to run non-electric vehicles, there is plenty of untapped opportunity in this area. Small nudges to take the effort out of behavioural decisions could just be what the doctor ordered.

Built Environment: with great rental comes great liability

Tenants could be liable for buildings carbon footprint (Brink)

What is the big investing theme - Decarbonising our built environment is both important and challenging, especially around the question of who pays. Some change will be driven by government actions such as building codes, but some will come from tenants demanding change.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

With drivers such as the Inflation Reduction Act increasing the importance of reducing the carbon footprint of the built environment, renters of office space could find themselves liable if the offices they lease fail to meet low carbon emission standards. Landlords will likely write provisions into leases to ensure that commercial tenants share in liabilities to meet standards. SEC draft rules for disclosing climate and transition risk bring that liability to the companies themselves.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

The built environment is an important area of focus for sustainability investing. It represents over one third of global final energy use, generates nearly 40% of energy-related Green House Gas (GHG) emissions (which in themselves are 75.6% of total GHG emissions) and consumes 40% of global raw materials.

Responsibility for managing emissions where there is a leased asset arrangement such as a company renting office space really comes down to what is in the lease and as the article suggests, more and more we will likely see provisions written in. Reporting is to some extent also determined by the lease.

A number of reporting protocols and standards including TCFD and the GHG Protocol require companies to account for and report all of their scope 1 (direct emissions from owned/controlled sources) and scope 2 (indirect from purchased energy). The proposed SEC Climate Disclosure Rule which in a reopened comment period is proposing that companies report Scope 3 if those emissions are material (or the company has a specific scope 3 target). Scope 3 emissions are thought to comprise more than 85% of a commercial real estate company’s entire carbon footprint including embodied carbon (from the developer), employee emissions (from commuting etc) and emissions from a tenant (from energy use). However, with a leased asset, there is a question mark over who should report (and be responsible for) emissions associated with the leased asset, in this case the office building.

GRESB uses the type of lease as the determining factor of whether emissions are scope 1,2 or 3. A finance or capital lease treats the asset as wholly owned by the tenant (strictly speaking lessee) and it would be on their balance sheet, whilst an operating lease does not confer the risks and rewards of ownership. The GHG Protocol differentiates between a financial control approach or an operational control approach to both finance and operational leases (yes I know, it is getting quite complicated!).

So, if a financial control approach is used then if the lease is an operating lease, the lessee/tenant classifies emissions associated with fuel combustion and use of purchased electricity as scope 3. In all other cases they are scope 1 (for the combustion) and scope 2 (for the purchased).

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

Beyond carbon emissions, there is a higher level debate about responsibility for the supply chain (or downstream value chain including sales and distribution). And despite what you might read in the press, supply chain risk doesn’t just include manufacturing or sourcing from remote countries.

The German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, otherwise known as Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz or LKSG, aims to improve companies’ global supply chain compliance with human rights and material standards of environmental protection. It will come into force on 1st January 2023. Companies will have to review their supply chains, identify concrete supply chain risks, how best to handle those risks and put regular reviews in place. Fines for non-compliance are material with both financial (up to 2 percent of average global annual turnover where that turnover is > EUR400 million) and potential exclusion from public tenders for up to three years. Noteworthy for investors!

Electricity generation: flow batteries for long term storage

World's largest flow battery opens in China (Cosmos)

What is the big investing theme - 100% (or close to) renewable/low carbon electricity generation systems are looking more viable with each passing year, supported in many cases by long distance interconnectors. But one of the biggest barriers to widespread adoption remains the requirement for economic forms of electricity/energy storage. Li Ion batteries look to be the preferred short and medium storage period technology of choice but coping with infrequent low wind/low solar days will need long duration solutions.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

The Dalian Flow Battery Energy Storage Peak-shaving Power Station, in Dalian in northeast China, has just been connected to the grid, and will be operating by mid-October. The vanadium flow battery currently has a capacity of 100 MW/400 MWh, which will eventually be expanded to 200 MW/800 MWh.

According to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who helped develop the project, it can supply enough electricity to meet the daily demands of 200,000 residents. It will be used to smooth peaks and troughs in Dalian’s electricity demand and supply, making it easier to use solar and wind power.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

Battery storage, either standalone or integrated into solar and wind farms, is going to be an essential element of most countries plans to hit high levels of renewable electricity generation. BNEF’s 2021 Global Energy Storage Outlook estimates that a massive 345 gigawatts/999 gigawatt-hours of new energy storage capacity will be added globally between 2021 and 2030. The report suggests that the majority, or 55%, of energy storage build by 2030 will be to provide energy shifting (for instance, storing solar or wind to release later).

The technology of choice for shorter durations is Li Ion, which already dominates the storage market out to six or even eight hours. So, this comfortably covers the windless evening peak on a typical day. However, in the coming years as storage is deployed to replace higher capacity factor conventional generation, absorb longer periods of renewable overgeneration, and support resilience during severe weather events, there is a potential need for longer duration storage.

Because the cost of lithium-ion batteries increases proportionally as a systems’ duration increases, larger systems are currently very expensive. Longer duration battery technologies like vanadium flow and iron flow have a more marginal increase in cost as you increase the duration, and so are more cost competitive as you get to larger system sizes.

How big a market could this be? The industry group, the Long Duration Energy Storage Council forecasts US$50bn cumulative investment by 2025 achieving 1 TWh of LDES; US$200-500bn by 2030 achieving 5-10 TWh; and $1.1-1.8bn by 2035 achieving 35-70 TWh. But it concedes that LDES costs must decrease by 60% for it to be cost optimal. The average installed duration globally is expected to reach 14 hours by 2030 and a whopping 64 hours between 2030-2040, so potentially outcompeting Li Ion.

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

For investors, we suggest there are three issues to bear in mind. First, watch China. This could turn out to be yet another renewable technology where Chinese producers dominate. What might mitigate this - demand in the US. The current political environment supports domestic production, so it’s possible we could see a US champion.

Second, be aware of the when this might happen. Forecasts suggest that flow batteries potentially really come into their own when electricity grids have high levels of renewable generation, which is when the higher cost longer duration flexibility they offer becomes most valuable. So maybe the late 2020’s and into the 2030’s.

Third, keep in the back of your mind that Li Ion (and its variants) might just keep getting better and better, pushing technologies like flow batteries out to solving the really long duration challenges. It was only a few years ago that Li Ion was seen as the sub 4 hour technology. Plus, there are other technologies such as pumped storage hydro and enhanced geothermal also eyeing up this market.

Luxury Goods: the rise of resale?

Luxury resale - owning the customer or partnering with the brand (Forbes)

What is the big investing theme - all of the retail/consumer goods industries need to adapt to new ways of producing, distributing, selling and then disposing of their goods. Socially, this is a challenging sector in which to drive change. While some sections of the population are becoming more aware of the damages the industry imposes, others focus purely on low cost, best illustrated by the growth of fast fashion.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

Is the format battle for the luxury resale market coming to a conclusion? Just about the time that The RealReal started to appear on high-risk lists for bankruptcy, one of its rivals, Reflaunt, announced a new partnership with luxury goods companies Balenciaga and Saks Off 5th for its resale-as-a-service offering. Both The RealReal and Reflaunt compete in the same $32 billion secondhand luxury market that Bain reports grew five-times faster than the primary market from 2017 to 2021, up 65% as compared to 12% for first hand personal luxury. But the companies operate under totally different business models.

The RealReal follows a more or less traditional consignment business model. The individual consigner (reseller) sends an item to The REAL where it may be sold on or bought directly for cash or site credit. Reflaunt operates quite differently under a resale-as-a-service model (RaaS.) Essentially it is a facilitator for brands and retailers to seamlessly integrate resale and circular fashion directly into their own business models. While it does offer consumers direct consignment through its concierge service and direct trade-in on a limited basis, brands are its primary target.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

As an ex consumer goods analyst and investor, I have always found the luxury market fascinating. At one level it moves slowly. Tradition and heritage are very important, and companies are very reluctant to do anything that might damage their brand. But move it does. For instance, over time online has gradually grown - although obviously it’s still nowhere as large in terms of market share as in apparel or other retail categories.

You might think that the luxury goods brands are largely protected from the sustainability debate. Maybe for now, but that is also changing. For instance, interest in vintage luxury goods is growing and growing fast. For vintage, read second hand, but that’s not a term that the luxury market will use. This is about selling on your (well-loved but now not wanted) branded handbag or other luxury item. Branded luxury watches have had an established secondhand market for some time. But the vintage theme goes further, and its growing and fast.

As Claire Kent (twenty years an equity analyst, nine years of them top ranked for her coverage of the luxury sector and now a consultant) highlights in a recent report, “although there are many reasons why vintage has become so popular, perhaps the most important reason is certain consumers’ (especially Gen Z’s) growing interest in helping the environment, purchasing more responsibly, and fueling the circular economy.”

For the luxury goods companies this trend is both an opportunity and a threat. As Claire points out in her report, by the end of the decade (not a long time for a luxury company) Gen Z will have replaced millennials as the number one consumers of luxury. And the resale market could be a great entry point for the luxury companies, building a relationship with the new Gen Z consumers, who could move on over time to buy first hand items. The threat is also there. Leaving the market to the resellers could, over time, give the up coming consumer different choices about where they buy their luxury goods. Choices that have less of a role for the luxury brands.

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

Looking at adjacent industries, the apparel market (especially fast fashion) is coming under increasing scrutiny over its environmental and social impacts. According to a recent report from the World Resources Institute and others, it is estimated that the apparel sector emitted 1.0 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 e) in 2019, or roughly 2 percent of annual global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (we have seen higher estimates from other sources).

Left unchecked, emissions are forecast to grow to 1.6 Gt by 2030, well off the pace needed to deliver the 45 percent absolute reduction needed to limit warming to 1.5°C. When you add in water use, with it apparently taking 6,000 liters of water to make 1kg of cotton, and labour/human rights issues, it’s not surprising that the industry is facing increasing scrutiny.

No one is arguing that growing the resale market is the total sustainability solution for the luxury market, but it can play an important role. Resale means less primary raw materials are needed, and it leads to more repair and refurbishment, feeding into a more circular economy approach. Yes, there are risks, especially around the potential cannibalisation of first hand buying, and brand reputation. And there are potential dead ends, such as blockchain. But resale is here to stay, and luxury companies need to find a way to make it work for them.

Human Rights: are we doing enough about modern slavery

50 million people worldwide in modern slavery (ILO)

What is the big investing theme - What is now widely known as modern slavery is rapidly becoming the next big ESG investing theme. Many investors allocate to ESG funds because they want their investing to align with their values, and they expect statements of intent to be followed up with action. Plus, it’s now becoming a legal issue. Countries are increasingly implementing the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights into national legislation, making companies responsible for human rights abuses in their supply chains. And hence courts are increasingly getting involved.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

The ILO (the International Labour Organization), the IOM (The International Organization for Migration) and Walk Free have released a new report estimating that there are 50 million people in situations of "modern slavery" on any given day, either forced to work against their will or in a marriage that they were forced into. This number translates to nearly one of every 150 people in the world. The estimates also indicate that situations of modern slavery are by no means transient – entrapment in forced labour can last years. And, in most cases forced marriage is a life sentence.

The UN's labour organisation stressed that slavery is not confined to poor countries far away from the Western world - more than half of all forced labour happens in wealthier countries in the upper-middle or high-income bracket. They estimate that about 27.6 million people are in forced labour, of which women and girls make up 11.8 million. The total set out includes 3.3 million children, with more than half in commercial sexual exploitation. And sadly, the situation is not improving.

Our take on this

Why is this important ?

The 2021 global estimates show that millions more men, women, and children have been forced to work or marry in the period since the previous estimates were released in 2017. Through the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the global community has committed to ending modern slavery among children by 2025, and universally by 2030 (Target 8.7).

This report underscores the scale of the challenge facing the global community in the short period remaining to meet these ambitious targets. This is despite the surge in investments being channeled into ESG funds. We can see this issue becoming an ESG touchstone, with sustainability focused clients looking to their asset managers to undertake more and sustained engagement. They will increasingly be looking for impact, clear and concrete outcomes, with policies actually being turned into action on the ground.

Plus, this is no longer a values-based issue, breaches can also have a financial dimension. Moves such as the upcoming German supply chain law (Lieferkettengesetz) mean that companies will need to “perform various due diligence procedures in order to monitor, prevent and ameliorate potential human rights abuses in their supply chains.” And courts are increasingly willing to impose a common law duty of care on parent companies for the wrongful acts of their international subsidiaries.

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of

The rise in numbers of people in modern slavery is due to an increase in the use of forced labour and exploitation in the private sector. This suggests that there are a number of things which are NOT being done in terms of due diligence with regard to exploitation, meaningful community engagement, living wages, ensuring non-discrimination.

Some actions such as protecting people from hazardous work or creating a policy around living wages, parental leave or protection from abuse and discrimination, can be accomplished on a relatively short timeline. But addressing the more engrained societal root causes around poverty, lack of education, lack of access to health care, as well as creating effective internal mechanisms to address complaints, encourage whistleblowers, and provide appropriate redress, need to have a longer-term focus. This is going to take a lot more resource, with material inputs from subject experts. It will no longer be ok to rely on companies self-reported actions. One question this raises is how this will fit into a passive or quant-based model of fund management.

Finally, the term "modern slavery" legally means very little, and its use can actually be quite problematic, although we understand its power as an advocacy tool. Our preference is that investors use the definition of forced labour as set out in the ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No.29), which refers to “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”

Emissions: revisiting the orphan wells

Abandoned Texas oil wells - the state won't fix them(Floodlight)

What is the big investing theme - If we are to reduce O&G usage, there will be a whole series of costs we as a society may need to face. Some are to do with compensation for stranded assets (an unpopular topic) and some are to do with cleaning up the existing infrastructure. This is a theme that could get material and run for many decades.

In a nutshell - what does the story say

The Texas Railroad Commission would normally take responsibility for cleaning up orphaned oil and gas wells (abandoned by previous owners and where ownership is hard to confirm). However, where unproductive wells were previously transferred as water wells (“P-13 wells”) the Commission argues that they are not oil & gas wells and therefore not their responsibility.

Revisiting the theme

We previously wrote about the issue of orphaned wells in issue 40 of The Sustainable Investor. Pertinent to this story, where a ranch owner’s land and cattle were being contaminated by leaks causing both immediate financial harm and health risk: “given that many orphaned wells will have changed ownership many times before being abandoned, the likelihood that they are in disrepair is high and hence potentially an important source of leakage. Given methane’s near term advanced warming potential, the benefits of prioritising and plugging are clear. One question is - who pays? If it’s the government there is the obvious moral hazard issue, and also the time scale for action. But it’s also worth asking if we can find financial incentives to get the private sector to accelerate the process.”

Now the legal stuff. Our blogs and all website content are solely for informational purposes and should not be construed as investment research (as defined by the FCA and other regulators). Nor does it have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient - it's not investment advice. We (being the writers of The Sustainable Investor blogs and the publishers of related websites) do not promote funds or suggest you buy or otherwise invest in specific securities or other financial instruments. Any reference to a company is illustrative only and should not be seen as a recommendation or a comment on valuation. You should not rely on the blogs, data or other information provided for making financial decisions. You should consult with an appropriate professional for specific advice tailored to your situation and/or to verify the accuracy of the information provided herein prior to making any investment decisions.